How fake images change our memory and behaviour

- Rogues gallery

- Doctored images emerged as Hurricane Sandy hit New York earlier this year. History shows this is far from the first time people have tried to manipulate our minds in this way.

Doctored images can affect what we eat, how we vote and even our

childhood recollections. The question scientists are asking is why

there’s nothing we can do to stop it.Exhibition shows photo tricks

The year was a memorable one – looking back at the unforgettable images over the past 12 months, you might think of apocalyptic-looking clouds over Manhattan during Hurricane Sandy, or Mitt Romney’s children mistakenly standing in a line spelling out the word “MONEY”, or even the winning US Powerball lottery ticket that became the most shared picture on Facebook. There’s only one problem. All these images are fake.It would be fine if we could dismiss these images as a fleeting joke, an amusing but harmless tidbit shared among our friends and followers, if it weren’t for the fact that our minds appear to have a curious but fundamental glitch. People tend to think of their memories as a transcript, a rough history of events from some early age until the very moment they are experiencing. But human memory is far more like a desert mirage than a transcript – as we recall the past we are really just making meaning out of the flickering patterns of sights, smells and sounds we think we remember.

For decades, researchers have been exploring just how unreliable our own memories are. Not only is memory fickle when we access it, but it's also quite easily subverted and rewritten. Combine this susceptibility with modern image-editing software at our fingertips like Photoshop, and it's a recipe for disaster. In a world where we can witness news and world events as they unfold, fake images surround us, and our minds accept these pictures as real, and remember them later. These fake memories don't just distort how we see our past, they affect our current and future behaviour too – from what we eat, to how we protest and vote. The problem is there’s virtually nothing we can do to stop it.

Old memories seem to be the easiest to manipulate. In one study, subjects were showed images from their childhood. Along with real images, researchers snuck in doctored photographs of the subject taking a hot-air balloon ride with his or her family. After seeing those images, 50% of subjects recalled some part of that hot air balloon ride – though the event was entirely made up.

In another experiment by Elizabeth Loftus, one of the pioneer researchers in the field of altered memories, researchers showed people advertising material for Disneyland that described one visitor shaking hands with Bugs Bunny. After reading the story, about a third of the participants said they remembered meeting or shaking hands with Bugs Bunny when they had visited Disneyland. But Bugs Bunny doesn't live in Disneyland – he's a Warner Brothers character. None of those people had ever met Bugs, but seeing images of him and reading the story made them remember something entirely fabricated.

Childhood memories may be the easiest to manipulate, but recent, adult memories are at risk too. In one experiment, researchers asked participants to take part in a gambling task alongside a partner. When they came back for the second part of the experiment, they were shown doctored footage of their partner cheating. Despite not actually having seen their partner cheat, 20% of participants were willing to sign a witness statement saying that they had. Even after being told that the footage was doctored, participants sometimes recalled the cheating that never happened. “They say things like ‘I remember seeing it, I saw them taking too much money’,” says Kimberly Wade, a memory researcher from the University of Warwick, who carried out the study.

Political trickery

Of course, people aren’t walking around doctoring false images of your childhood or your recent past, but you've probably seen thousands of doctored photographs in your lifetime without you knowing it. From advertisements to political campaigns, altered and faked images surround us every day. Restaurants make their food look more appetising, magazines make their models skinnier and blemish free, colleges and politicians splice people into photographs to make their students and crowds look more diverse.

In political campaigns especially, faked images show up again and again. In one famous photograph that surfaced during the 2004 US election campaign, Senator John Kerry is sitting next to Jane Fonda, with the caption explaining that both Kerry and Fonda were at a Vietnam war protest. The New York Times cited the image, and many anti-Kerry blogs and sites displayed it prominently. The problem is, the photograph is a fake. John Kerry and Jane Fonda were never at any anti-war protest together – someone had combined two different photographs.

More recently, a photograph surfaced of Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney's children, who each wore a shirt with one letter of their last name. The children mistakenly lined up spelling out “MONEY”, rather than “ROMNEY”. Or at least that's what the picture will have you believe. In reality, the children lined up properly, spelling their own last name, and someone later simply switched the letters on the image.

But like a balloon ride or Bugs Bunny, these fake images can have very real effects on memory. In 2010, the online magazine Slate ran an experiment showing readers a handful of political photographs. Some of them were of real events, while others were doctored. Readers were then asked whether or not they remembered those events happening. Nearly half of Slate's readers claimed they remembered the fake political events happening. And that's in an uncontrolled setting, where they could have easily cheated and looked up the answers. Many people are adamant that John Kerry and Jane Fonda protested together, simply because they saw that photograph.

Seeing these fake images goes even beyond altering our memory of events. It can actually change our behaviours too. One study convinced people that egg salad had made them sick in their childhood. Four months later those participants were less likely to want to eat egg salad, even though the memory that made them feel that way was entirely false.

Another study showed participants images of two different protests – some from the 1989 protests in Tiananmen Square, others from 2003 anti-war protests in Rome. The researchers doctored some of the images to make the protests more crowded and violent than they really were. When asked about the events later, not only did the participants remember the protests being violent, but they also expressed more hesitance to attend a protest in the future. And when asked for comments about the events, people wrote about conflicts, damage to property and injuries from the police and participants that were never documented at the time of the event.

Whether or not these sorts of false images could radically change someone's mind on political issues has yet to be proven, says Steven Frenda, a memory researcher from the University of California in Irvine, who has a forthcoming paper examining the results of the Slate survey. But he thinks “yet” is the operative word. "I believe it probably is true,” he says, “but we don't have the evidence to say that." Researchers are still pushing the limits of just how far they can go with doctored photographs, Frenda says, and they’re planning some experiments to assess whether long-held political beliefs can be swayed by faked imagery.

Why we're fooled

Images are really good at fooling our memories for a number of reasons, Wade says. A big part of it is because people trust photographs. "We still think of them as frozen moments in time," she says, even though most people know that photographs can be, and often are, doctored. In fact, people trust photographs so much that they actually place more weight on information that is accompanied with an image, regardless of how related or useful that image is. If you show participants a statement, and an image that provides no proof of that statement, they are far more likely to find that statement true than if it had no image alongside it.

And there are certain things that make a fake image more believable and more likely to be imprinted on our memories. People are more liable to be persuaded by false images that add weight to their beliefs. So those who were already opposed to John Kerry were quick to buy into the image of him and Jane Fonda protesting the war. Democrats are more likely to remember the Romney/Money mix-up. The Slate study found that Republicans were more likely to remember Barrack Obama shaking hands with Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, while Democrats are more likely to remember that George Bush was on vacation with the baseball pitcher Roger Clemens during Hurricane Katrina, even though neither event really happened.

Another reason we’re duped so readily is that we're really bad at telling fake photographs from real ones, says Hany Farid, an image doctoring expert from Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, United States. "It turns out that while the brain and the visual cortex is very good at many things, like face recognition, it is really really bad at analysing lighting and reflections." When presented with doctored images, humans are remarkably inept at telling which ones are fake and which are real. And we're bad in both directions, Farid says, judging fake images to be real, and real ones to be fake.

What's worse is that even when we're told the photographs we've seen are wrong, it doesn't seem to help. One of the first things that fades in our memory is where the information came from. Which is why you probably can’t remember who first told you that joke that you tell all the time, says Wade. "When we're faced with doctored images, even if up front if we know they’re fake, over time we may remember the image but not remember knowing that it's doctored.”

Brain games

In the end, there's not much anyone can really do to guard against being duped by these images, says Wade. Her lab has done studies in which subjects are told that they're about to see both fake and real images. Even with the warning, people will still remember the fake photographs as real. "Warnings don't seem to have much of an effect," she says, "that's how powerful some of these fake photo manipulations can be."

Reverse image searching online can reveal fakes, but time can erase that extra context. And even with specialisation and technology, verifying an image can be nearly impossible. "Proving that something is fake is possible," says Farid, "but proving the image is authentic is virtually impossible." All experts like Farid can really say is whether or not they could find evidence of tampering.

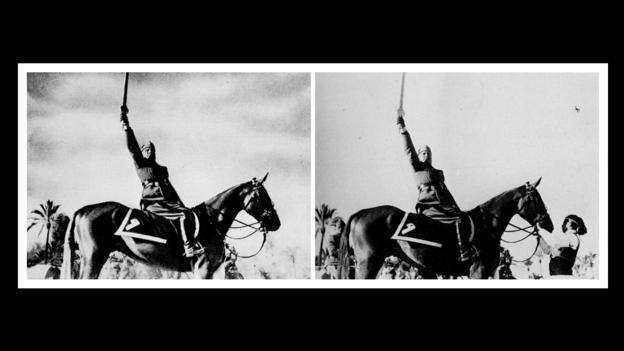

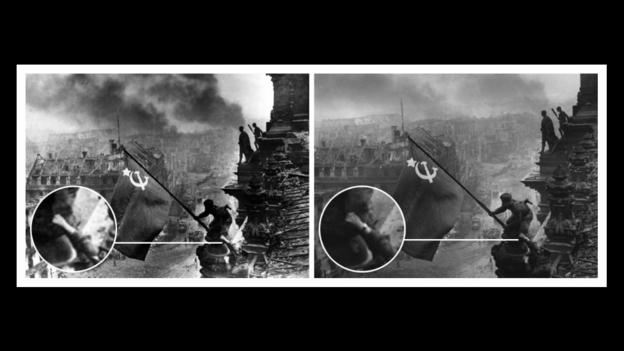

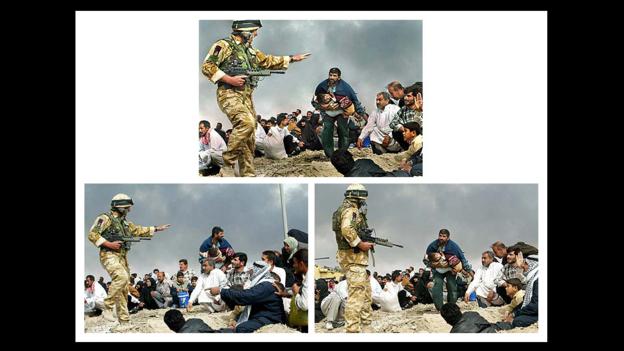

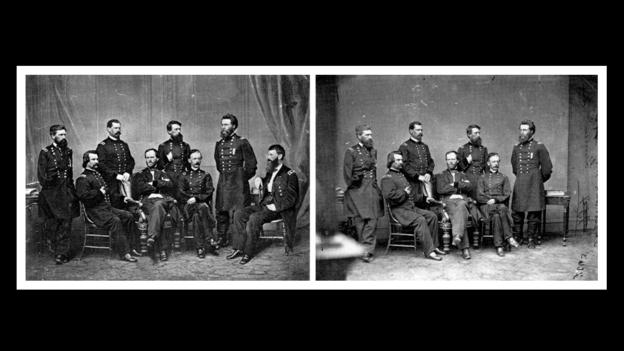

The worry is that with images pouring in from citizen reporters from all parts of the globe, people will be confronted with more doctored images, not less. But as Farid points out, photographers have always been doctoring images in some way. They choose what to frame, what to photograph, what moment to capture and what to crop out. And some famous photographers have staged their photographs not in post-processing, but in real time. In one famous photograph from the Crimean War, bombs littered the road. But the photographer had moved them there, to make things look more dramatic. Many of Mathew Brady’s famous photographs of the American Civil War were staged, the photographer dragging bodies about to make things more gruesome. You could call these contrived, or perhaps even fake, but these images would have passed even the most rigorous of image doctoring tests.

Yet, the way we remember events has a lot to do with the photographs that go with them – from Dorothea Lange’s classic image of a mother during the Dust Bowl, to the single man standing up against tanks in Tiananmen Square. Many probably remember Romney’s Money gaff that wasn’t, or images from Hurricane Sandy that never happened, just as well as they remember real images. When asked in the future, they’ll recall those pictures, and they’ll swear they remember those things happening. "That's the most fascinating thing about memory," says Frenda, "the way that it can be so flagrantly non-factual, but we have really high confidence in the accuracy of it." And it seems there’s nothing anybody can do about it.